How to Simulate Gravitational Waves in a Python Sandbox

Gravitational waves are one of the most fascinating predictions of Einstein’s General Relativity. They are ripples in the fabric of spacetime, caused by accelerating massive objects like merging black holes or neutron stars. Detecting them, as LIGO and Virgo have done, is a monumental feat of engineering and science.

But how do you even begin to visualize something as abstract as spacetime stretching and squeezing? You can’t just draw a picture. This is where a computational sandbox comes in handy.

Note: This post will not derive gravitational waves from Einstein’s field equations. That’s a thesis project in itself! Instead, we’ll build a simplified, conceptual simulation to visualize the effect of a gravitational wave on a collection of test particles. Think of it as a “toy model” designed for understanding, not for cutting-edge astrophysical research. We’re modeling the strain that a passing wave induces.

The Core Concept: Spacetime Strain

Imagine a grid of points representing spacetime. When a gravitational wave passes through this grid, it stretches space in one direction while simultaneously compressing it in a perpendicular direction. This effect then oscillates, leading to a dynamic distortion.

The simplest type of gravitational wave polarization is the “plus” (+) polarization. If the wave propagates along the z-axis, it will stretch along the x-axis and compress along the y-axis, then swap, doing the opposite.

Mathematically, a simplified gravitational wave strain $h(t)$ can be modeled as a simple oscillating function, for example:

$$ h(t) = H_0 \cos(\omega t) $$Where:

- $H_0$ is the amplitude of the wave. Real gravitational waves have incredibly tiny amplitudes (e.g., $10^{-21}$), but we’ll exaggerate this for visualization.

- $\omega$ is the angular frequency of the wave.

- $t$ is time.

If we consider a point at $(x, y)$ in our 2D plane, the effect of a passing “plus” polarized gravitational wave (propagating perpendicular to this plane) on its coordinates can be approximated as:

$$ x_{new} = x (1 + h(t)) \\ y_{new} = y (1 - h(t)) $$This model captures the essence of the stretching and squeezing without getting bogged down in tensors and field equations.

Setting Up Your Python Sandbox

You’ll need a few common Python libraries for numerical operations and plotting: numpy and matplotlib.

First, ensure you have them installed:

pip install numpy matplotlibStep-by-Step Simulation

We’ll build our simulation in a few logical steps:

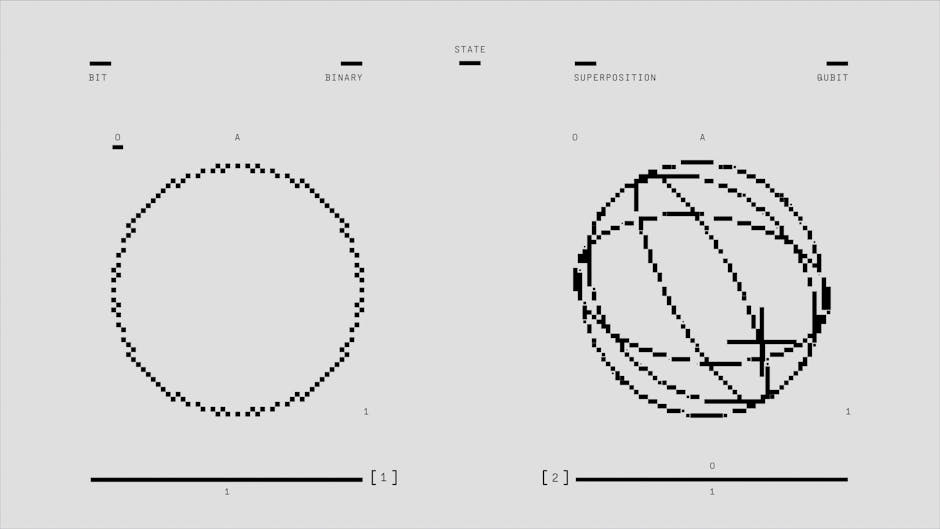

- Define the initial “spacetime” grid: We’ll start with a circle of points, as its deformation is visually striking.

- Create the gravitational wave function: A simple cosine wave.

- Animate the deformation: Use Matplotlib to update the points over time.

1. Initialize the Spacetime Grid (A Circle of Points)

We’ll generate points that form a perfect circle using numpy.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

# --- Simulation Parameters ---

NUM_POINTS = 1000 # Number of points in our 'spacetime' grid

RADIUS = 1.0 # Initial radius of our circleNow, let’s create the initial points:

# Generate points for a circle

theta = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, NUM_POINTS, endpoint=False)

initial_x = RADIUS * np.cos(theta)

initial_y = RADIUS * np.sin(theta)

# Combine into a single array for easier manipulation

initial_points = np.array([initial_x, initial_y])

print(f"Initial points shape: {initial_points.shape}")

print(f"First 5 X coordinates: {initial_x[:5]}")

print(f"First 5 Y coordinates: {initial_y[:5]}")Initial points shape: (2, 1000)

First 5 X coordinates: [1. 0.99995066 0.99980267 0.99955609 0.99921099]

First 5 Y coordinates: [0. 0.0062831 0.01256627 0.01884931 0.02513222]This gives us two arrays, initial_x and initial_y, representing the coordinates of 1000 points arranged in a circle.

2. Define the Gravitational Wave Function

Let’s define the parameters for our simulated gravitational wave. We’ll exaggerate the amplitude considerably to make the effect visible.

# --- Gravitational Wave Parameters ---

AMPLITUDE = 0.1 # Exaggerated amplitude (e.g., 0.1 for 10% strain)

FREQUENCY = 1.0 # Hz (how many cycles per second)

DURATION = 10.0 # seconds (total simulation time)

FPS = 30 # Frames per second for the animationNow, we can calculate the strain h(t) for any given time t:

def gravitational_wave_strain(t, amplitude, frequency):

"""

Calculates the strain h(t) of a simplified gravitational wave.

"""

# Using cosine for a wave starting at maximum effect

return amplitude * np.cos(2 * np.pi * frequency * t)

# Example at t=0 and t=DURATION/2

t_example_0 = 0

t_example_mid = DURATION / 2

print(f"Strain at t={t_example_0}s: {gravitational_wave_strain(t_example_0, AMPLITUDE, FREQUENCY):.4f}")

print(f"Strain at t={t_example_mid}s: {gravitational_wave_strain(t_example_mid, AMPLITUDE, FREQUENCY):.4f}")Strain at t=0s: 0.1000

Strain at t=5.0s: 0.1000Note: The example output for t=5.0s showing 0.1000 means that 2 * np.pi * frequency * t resulted in a multiple of 2 * np.pi, making cos return 1. This is expected for a FREQUENCY of 1.0 and t being an integer or half-integer if the period is 1 second.

3. Animate the Deformation

This is the fun part! We’ll use matplotlib.animation.FuncAnimation to update the plot frame by frame.

# --- Matplotlib Setup ---

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 6))

line, = ax.plot([], [], 'o', markersize=2, alpha=0.7) # Use 'o' for points

# Set plot limits (slightly larger than initial radius to see distortion)

ax.set_xlim(-(RADIUS * (1 + AMPLITUDE * 1.1)), (RADIUS * (1 + AMPLITUDE * 1.1)))

ax.set_ylim(-(RADIUS * (1 + AMPLITUDE * 1.1)), (RADIUS * (1 + AMPLITUDE * 1.1)))

ax.set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box') # Maintain aspect ratio for accurate visualization

ax.set_title("Simulating Gravitational Wave Strain")

ax.set_xlabel("X (arbitrary units)")

ax.set_ylabel("Y (arbitrary units)")

ax.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

# Hide axis ticks for a cleaner look

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

# --- Animation Function ---

def animate(frame):

"""

Update function for the animation.

Calculates the new positions of points based on current time and strain.

"""

time = frame / FPS # Current time in seconds

# Calculate the current gravitational wave strain

h_t = gravitational_wave_strain(time, AMPLITUDE, FREQUENCY)

# Apply the strain to the initial points

# x_new = x * (1 + h(t))

# y_new = y * (1 - h(t))

deformed_x = initial_x * (1 + h_t)

deformed_y = initial_y * (1 - h_t)

# Update the plot data

line.set_data(deformed_x, deformed_y)

return line,

# Create the animation

ani = animation.FuncAnimation(

fig,

animate,

frames=int(DURATION * FPS), # Total number of frames

interval=1000 / FPS, # Delay between frames in ms

blit=True, # Optimized drawing, only redraws what's changed

repeat=True # Loop the animation indefinitely

)

plt.show()

# Optional: Save the animation as a GIF (requires ImageMagick or Pillow)

# ani.save('gravitational_wave_sim.gif', writer='pillow', fps=FPS)

# print("Animation saved as gravitational_wave_sim.gif")Running the Full Simulation Script

Combine all the code blocks into a single file, for example, grav_wave_sim.py:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import matplotlib.animation as animation

# --- Simulation Parameters ---

NUM_POINTS = 1000 # Number of points in our 'spacetime' grid

RADIUS = 1.0 # Initial radius of our circle

# --- Gravitational Wave Parameters ---

AMPLITUDE = 0.1 # Exaggerated amplitude (e.g., 0.1 for 10% strain)

FREQUENCY = 0.5 # Hz (how many cycles per second)

DURATION = 10.0 # seconds (total simulation time)

FPS = 30 # Frames per second for the animation

# --- Initial Grid Setup (A Circle of Points) ---

theta = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, NUM_POINTS, endpoint=False)

initial_x = RADIUS * np.cos(theta)

initial_y = RADIUS * np.sin(theta)

# --- Gravitational Wave Strain Function ---

def gravitational_wave_strain(t, amplitude, frequency):

"""

Calculates the strain h(t) of a simplified gravitational wave (plus polarization).

"""

# Using cosine for a wave starting at maximum effect (or slightly offset for variety)

# The 2*pi*frequency converts frequency in Hz to angular frequency.

return amplitude * np.cos(2 * np.pi * frequency * t)

# --- Matplotlib Animation Setup ---

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 7))

line, = ax.plot([], [], 'o', markersize=2, alpha=0.7, color='skyblue')

# Set plot limits (slightly larger than initial radius to clearly see distortion)

# We multiply by 1 + AMPLITUDE * 1.1 to give some margin around the maximum expected stretch

max_coord = RADIUS * (1 + AMPLITUDE * 1.1)

ax.set_xlim(-max_coord, max_coord)

ax.set_ylim(-max_coord, max_coord)

ax.set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box') # Crucial to show proper circle/ellipse distortion

ax.set_title(f"Simulating Gravitational Wave Strain (Amp: {AMPLITUDE}, Freq: {FREQUENCY} Hz)")

ax.set_xlabel("X (arbitrary units)")

ax.set_ylabel("Y (arbitrary units)")

ax.grid(True, linestyle='--', alpha=0.6)

# Hide axis ticks for a cleaner, more abstract look

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

# --- Animation Function ---

def animate(frame):

"""

Update function for the animation.

Calculates the new positions of points based on current time and strain.

"""

time = frame / FPS # Current time in seconds

# Calculate the current gravitational wave strain

h_t = gravitational_wave_strain(time, AMPLITUDE, FREQUENCY)

# Apply the strain to the initial points for 'plus' polarization

# x_new = x * (1 + h(t))

# y_new = y * (1 - h(t))

deformed_x = initial_x * (1 + h_t)

deformed_y = initial_y * (1 - h_t)

# Update the plot data

line.set_data(deformed_x, deformed_y)

return line, # Return the updated artist for blitting optimization

# Create the animation

ani = animation.FuncAnimation(

fig,

animate,

frames=int(DURATION * FPS), # Total number of frames

interval=1000 / FPS, # Delay between frames in ms (e.g., 1000/30 for 30 FPS)

blit=True, # Optimize drawing by only updating changed parts

repeat=True # Loop the animation indefinitely

)

print("Starting gravitational wave simulation...")

plt.show()

# Optional: Save the animation as a GIF (requires Pillow installed: pip install Pillow)

# Uncomment the following lines if you want to save the animation.

# try:

# print(f"Saving animation to gravitational_wave_sim.gif (this may take a moment)...")

# ani.save('gravitational_wave_sim.gif', writer='pillow', fps=FPS, dpi=100)

# print("Animation saved successfully!")

# except Exception as e:

# print(f"Error saving animation: {e}. Make sure you have Pillow installed (`pip install Pillow`).")To run this, save it as grav_wave_sim.py and execute from your terminal:

python grav_wave_sim.pyStarting gravitational wave simulation...

# A Matplotlib window will open, displaying the animation.

# If you uncommented the save part:

# Saving animation to gravitational_wave_sim.gif (this may take a moment)...

# Animation saved successfully!You should see a circle of points rhythmically stretching along one axis and compressing along the perpendicular axis, then reversing. This is the visual representation of spacetime being distorted by a passing gravitational wave.

Understanding the Output and Limitations

The animation you’ve just run is a powerful conceptual aid. It shows the hallmark effect of a gravitational wave: differential stretching and squeezing of space.

What it does show:

- The characteristic “plus” polarization where perpendicular dimensions are affected inversely.

- The oscillatory nature of the wave.

- How even a simple set of points can illustrate complex physical phenomena.

What it doesn’t show (and why that’s okay for a sandbox):

- Propagation Speed: We are not modeling the wave traveling through space (e.g., at the speed of light). We are simply showing the effect at a single “location” over time.

- Energy and Amplitude Damping: Real gravitational waves lose energy as they spread, causing their amplitude to decrease. Our model has a constant amplitude.

- Source: The wave just “appears” with a set frequency and amplitude; it’s not generated by a merging black hole or neutron star system.

- Full General Relativity: This is a simplified kinematic model of the effect, not a solution to Einstein’s field equations. It ignores the intricate curvature of spacetime and only focuses on the linear strain.

- Cross Polarization: There’s also a “cross” (x) polarization, which is similar but rotated by 45 degrees. You could add this by applying similar transformations to

initial_xandinitial_yrotated by 45 degrees.

Further Exploration

This sandbox is just the beginning. Here are a few ideas to expand your understanding:

- Experiment with Parameters: Change

AMPLITUDE,FREQUENCY, orDURATION. What happens if the amplitude is tiny? What if the frequency is very high or very low? - Initial Grid Shape: Instead of a circle, try starting with a square grid of points using

np.meshgrid. This can also show the distortion in an interesting way. - Add Cross Polarization: Can you modify the

animatefunction to include a blend of plus and cross polarization, or switch between them?- For cross polarization:

x_new = x - h(t) * yandy_new = y + h(t) * x. This looks like a shear.

- For cross polarization:

- 3D Visualization (Advanced): If you’re feeling ambitious, you could try to extend this to 3D using

matplotlib.pyplot.scatterin a 3D projection, but handling rotations and projections can quickly become complex.

While this simulation is a conceptual abstraction, it provides a tangible way to grasp the elusive concept of spacetime distortion by gravitational waves. It’s a testament to how even simple models in Python can illuminate complex physical realities. Keep experimenting!