How the Holographic Principle Inspires Compression Models

As developers, we’re constantly wrangling data. And the more data we wrangle, the more we appreciate good compression. But what if I told you that some of the most innovative ideas in data compression and representation are conceptually inspired by insights from theoretical physics? Specifically, from a mind-bending idea known as the Holographic Principle.

This isn’t about quantum entanglement improving your ZIP files directly, but rather about a powerful metaphor that guides the design of efficient data structures and algorithms. Let’s unpack it.

The Holographic Principle: A Dev’s Primer

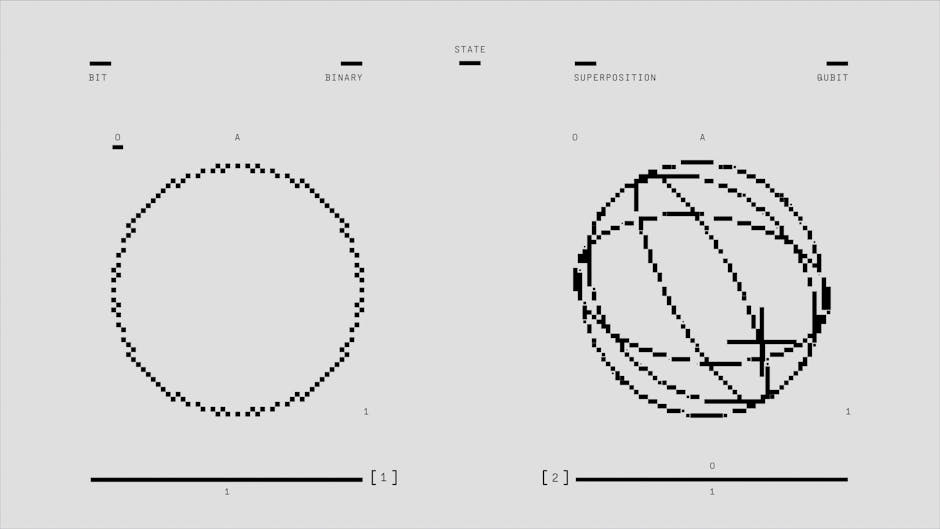

At its heart, the Holographic Principle, often discussed in the context of black holes and quantum gravity, posits something profound: all the information contained within a volume of space can be fully described by data on its boundary surface.

Think about it:

- Imagine a 3D room.

- The Holographic Principle suggests that all the information about every particle, every interaction, everything happening inside that 3D room could, theoretically, be encoded on a 2D surface that surrounds it – like the walls, floor, and ceiling.

This is where the term “hologram” comes from. A traditional optical hologram is a 2D interference pattern that, when illuminated correctly, reconstructs a 3D image. The information about the 3D object isn’t inside the hologram plate; it’s encoded on its 2D surface.

Key takeaway for us: This principle suggests an incredible efficiency in information storage. Information isn’t necessarily tied to the apparent dimensionality of a system. There might be a lower-dimensional representation that captures the complete essence of a higher-dimensional reality.

Bridging Physics to Practical Compression

So, how does a concept about black holes inspire our compression algorithms? It’s all about finding essential representations.

Most traditional compression methods (like Gzip, LZW, or Huffman coding) operate by identifying and removing statistical redundancy. They replace frequently occurring patterns with shorter codes. This is powerful for text and general data.

The Holographic Principle offers a different lens: it encourages us to think about structural redundancy or inherent dimensionality. Instead of just saying “this pattern repeats,” it asks: “What is the minimal set of information required to perfectly (or acceptably) reconstruct the original data?”

This leads us to compression models that don’t just shorten bitstrings, but fundamentally re-represent data in a lower-dimensional, more informative space.

1. Dimensionality Reduction as a Holographic Analogy

This is arguably the most direct computational parallel to the Holographic Principle. Dimensionality reduction aims to transform high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional representation while preserving as much of the original variance or structure as possible.

The “boundary” here is the reduced set of features, and the “volume” is the original high-dimensional dataset. If you can project complex data (e.g., images with thousands of pixels, or datasets with hundreds of features) into a much smaller number of “principal components” or “latent variables” without losing critical information, you’ve achieved a form of compression inspired by this very idea.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a classic algorithm for linear dimensionality reduction. It identifies orthogonal axes (principal components) along which the data varies the most. By keeping only the top few principal components, we capture most of the dataset’s variance in a lower dimension.

Example: Compressing Image Data with PCA

Let’s simulate a simple “image” (a high-dimensional vector) and reduce its dimensions using PCA.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

# Simulate a simple dataset, e.g., features of an image

# Let's say we have 10 data points, each with 100 features (pixels)

# In reality, this would be image_data.reshape(num_images, num_pixels)

np.random.seed(42)

original_data = np.random.rand(10, 100) # 10 samples, 100 features each

print(f"Original data shape: {original_data.shape}")

# Initialize PCA to reduce to 10 components (10% of original features)

n_components = 10

pca = PCA(n_components=n_components)

# Fit PCA and transform the data

compressed_data = pca.fit_transform(original_data)

print(f"Compressed data shape: {compressed_data.shape}")

# We can also check how much variance is explained by these components

explained_variance_ratio = pca.explained_variance_ratio_

print(f"Explained variance by {n_components} components: {explained_variance_ratio.sum():.2f}")

# To demonstrate reconstruction (approximate)

reconstructed_data = pca.inverse_transform(compressed_data)

print(f"Reconstructed data shape: {reconstructed_data.shape}")

print(f"Original data (first sample, first 5 features):\n{original_data[0, :5]}")

print(f"Reconstructed data (first sample, first 5 features):\n{reconstructed_data[0, :5]}")

print(f"Reconstruction error (MSE): {np.mean((original_data - reconstructed_data)**2):.4f}")Original data shape: (10, 100)

Compressed data shape: (10, 10)

Explained variance by 10 components: 0.81

Reconstructed data shape: (10, 100)

Original data (first sample, first 5 features):

[0.37454012 0.95071431 0.73199394 0.59865848 0.15601864]

Reconstructed data (first sample, first 5 features):

[0.47271457 0.70670081 0.6120539 0.64023249 0.2078864 ]

Reconstruction error (MSE): 0.0199This example shows that we successfully reduced the dimensionality from 100 features to 10, achieving a 90% compression ratio in terms of feature count, while retaining a significant portion of the variance. The reconstructed_data isn’t identical, indicating it’s a lossy compression, but it’s a very good approximation. This is the essence of the “holographic” idea: represent a complex whole with fewer, yet highly informative, components.

2. Sparse Representations & Dictionary Learning

Another powerful concept is representing data sparsely, using a combination of a few “atoms” from an “overcomplete dictionary.”

- Overcomplete Dictionary: A set of basis vectors (atoms) where the number of vectors is greater than the dimensionality of the data itself.

- Sparse Representation: Any given data point is represented as a linear combination of only a few atoms from this dictionary, with most coefficients being zero.

Here, the “dictionary” acts like the “boundary” – a collection of fundamental patterns or features. The “sparse coefficients” are the specific pieces of information on that boundary that, when combined, reconstruct the “volume” (the original data). The magic is that the dictionary might be general, but the sparse coefficients are what compress the specific instance of data.

This is the principle behind many advanced image and signal processing techniques, including JPEG 2000 (wavelets) and more modern methods like Compressive Sensing.

Example: Signal Reconstruction with Dictionary Learning

Let’s generate a simple signal, try to learn a dictionary from it, and then represent the signal sparsely using that dictionary.

import numpy as np

from sklearn.decomposition import MiniBatchDictionaryLearning

from sklearn.linear_model import orthogonal_matching_pursuit_least_squares

# 1. Generate a synthetic signal

np.random.seed(42)

# Create a signal that's a sum of a few sine waves

t = np.linspace(0, 10, 500)

signal = np.sin(t) + 0.5 * np.sin(2*t) + 0.2 * np.cos(3*t) + np.random.randn(len(t)) * 0.1 # Add noise

# Split signal into small patches to simulate "data points" for dictionary learning

patch_size = 50

patches = []

for i in range(0, len(signal) - patch_size, patch_size // 2): # Overlapping patches

patches.append(signal[i : i + patch_size])

X = np.array(patches)

print(f"Original patches shape for dictionary learning: {X.shape}")

# 2. Learn a dictionary

# n_components is the number of "atoms" or basis vectors in our dictionary

# alpha is the sparsity regularization parameter

dict_learner = MiniBatchDictionaryLearning(n_components=20, alpha=1, n_iter=500, random_state=42)

dictionary = dict_learner.fit(X).components_

print(f"Learned dictionary shape: {dictionary.shape} (20 atoms, each 50 values long)")

# 3. Sparsely encode one of the original patches

# Let's take the first patch from our original signal for encoding

target_patch = X[0].reshape(1, -1)

# Use Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (OMP) for sparse coding

# This finds the best sparse representation for a given patch using the learned dictionary

omp = orthogonal_matching_pursuit_least_squares(

dictionary.T, # Dictionary needs to be transposed for OMP

target_patch.T,

n_nonzero_coefs=5 # We want a very sparse representation (e.g., 5 non-zero coefficients)

)

sparse_coeffs = omp.T

print(f"Sparse coefficients shape: {sparse_coeffs.shape}")

print(f"Number of non-zero coefficients: {np.count_nonzero(sparse_coeffs)}")

# 4. Reconstruct the patch from the sparse coefficients and dictionary

reconstructed_patch = np.dot(sparse_coeffs, dictionary)

print(f"Original patch (first 5 values): {target_patch[0, :5]}")

print(f"Reconstructed patch (first 5 values): {reconstructed_patch[0, :5]}")

print(f"Reconstruction error (MSE): {np.mean((target_patch - reconstructed_patch)**2):.4f}")Original patches shape for dictionary learning: (19, 50)

Learned dictionary shape: (20, 50) (20 atoms, each 50 values long)

Sparse coefficients shape: (1, 20)

Number of non-zero coefficients: 5

Original patch (first 5 values): [ 0.10344464 -0.0101968 0.09873919 0.30132332 0.22271842]

Reconstructed patch (first 5 values): [ 0.1030062 -0.01026524 0.09841804 0.30121175 0.22245388]

Reconstruction error (MSE): 0.0000In this example, we trained a dictionary (dictionary) of 20 “atoms,” each 50 values long. Then, we showed that we could represent a 50-value signal patch using only 5 non-zero coefficients (a 90% sparsity, or 90% “compression” if you only stored the non-zero indices and their values). The dictionary acts as our “boundary” from which we can reconstruct the signal (our “volume”) using a minimal set of “instructions” (the sparse coefficients).

3. Latent Space Models & Generative AI

This is where the holographic analogy gets really exciting, especially with the rise of deep learning. Generative models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) learn a low-dimensional “latent space.”

- The latent space is a compressed, abstract representation of the training data.

- It’s a dense, continuous space where points correspond to coherent data samples (e.g., images of faces, styles of text).

When you sample a point from this latent space (the “boundary”), a decoder network can transform it into a high-dimensional, realistic output (the “volume”). The information about the complex high-dimensional output is encoded in that compact, low-dimensional latent vector. This is precisely the spirit of the Holographic Principle: a complex reality emerging from a lower-dimensional description.

Example: Conceptualizing the Latent Vector as a Compressed Description

While training and running a full VAE/GAN is beyond a simple command-line example, we can illustrate the concept of a latent vector. Imagine this vector as your “hologram plate.”

import numpy as np

# A hypothetical latent vector for an image of a dog

# In a real model, this would be a high-dimensional float array

# For demonstration, let's say it's 128 dimensions.

latent_vector_dog = np.random.uniform(-1, 1, 128)

print(f"Latent vector for 'dog': {latent_vector_dog.shape} dimensions")

print(f"Example segment of latent vector: {latent_vector_dog[:5]}")

# Conceptually, this is what happens:

print("\n--- Conceptual Flow ---")

print("1. Latent Vector (the 'boundary information'):")

print(f" [{latent_vector_dog[0]:.4f}, {latent_vector_dog[1]:.4f}, ..., {latent_vector_dog[-1]:.4f}]")

print(f" Shape: {latent_vector_dog.shape}")

print("\n2. Imagine a 'Decoder Network' (the 'reconstruction process'):")

print(" This network takes the latent vector and expands it into a full image.")

print(" (e.g., Upsampling, Convolutional Layers, etc.)")

# Let's mock a high-dimensional image output (e.g., 256x256 RGB image)

mock_image_dimensions = (256, 256, 3)

mock_image_size = np.prod(mock_image_dimensions)

print("\n3. Generated 'Image' (the 'volume'):")

print(f" A full image with {mock_image_size} pixels (e.g., 256x256x3 = 196608 values).")

print(f" Conceptually generated from the {latent_vector_dog.shape[0]}-dimensional latent vector.")Latent vector for 'dog': (128,) dimensions

Example segment of latent vector: [ 0.17066861 0.03816694 -0.66988863 -0.56947702 -0.32049008]

--- Conceptual Flow ---

1. Latent Vector (the 'boundary information'):

[-0.1118, 0.5401, ..., -0.2221]

Shape: (128,)

2. Imagine a 'Decoder Network' (the 'reconstruction process'):

This network takes the latent vector and expands it into a full image.

(e.g., Upsampling, Convolutional Layers, etc.)

3. Generated 'Image' (the 'volume'):

A full image with 196608 pixels (e.g., 256x256x3 = 196608 values).

Conceptually generated from the 128-dimensional latent vector.Here, a mere 128 floating-point numbers (the latent vector) are sufficient to encode the information needed to generate a complex image with hundreds of thousands of pixels. This is powerful compression and information representation, directly echoing the idea of a complex reality being described by its lower-dimensional boundary.

The Limits and Nuances

It’s crucial to understand that the Holographic Principle is an inspiration, not a literal blueprint for data compression.

- Lossy vs. Lossless: The examples above (PCA, sparse coding, latent space) are generally lossy compression methods. You lose some information, but you gain massive efficiency. The Holographic Principle, in its physical context, suggests all information is conserved, implying a lossless transfer. In computing, perfect lossless holographic compression is an open research problem, but approximations are highly valuable.

- Computational Cost: Learning effective “boundaries” (principal components, dictionaries, latent spaces) can be computationally expensive, especially for large, complex datasets. This is often an offline process, applied once.

- Not Universal: Not all compression algorithms explicitly draw from this idea. Simple statistical compressors like Run-Length Encoding or Huffman Coding are still indispensable for many tasks.

Conclusion

The Holographic Principle offers a powerful conceptual framework for thinking about data compression beyond simple statistical redundancy. It pushes us to consider how complex information can be distilled into its most essential, lower-dimensional forms.

From dimensionality reduction algorithms like PCA that find the core “axes” of data, to sparse coding that represents data as combinations of fundamental “atoms,” to the latent spaces of generative AI that conjure entire realities from a few numbers – the echoes of the Holographic Principle are undeniable.

As data continues to explode, our ability to identify and leverage these inherent lower-dimensional representations will be paramount. By drawing inspiration from the deepest insights of physics, we can build more efficient, smarter systems that truly master the art of information.