How the Fermi-Dirac Distribution Defines Modern Computing

As developers, we often interact with computing at a high level – writing code, deploying services, configuring systems. But beneath the layers of abstraction lies a universe governed by quantum mechanics, where the behavior of subatomic particles dictates whether our if statements execute, our data persists, or our CPUs hum along.

At the very heart of this microscopic world, enabling everything from the simplest diode to the most complex multi-core processor, is a concept from statistical mechanics: the Fermi-Dirac distribution. It’s not just an academic curiosity; it’s the fundamental principle that determines how electrons behave in materials, especially semiconductors, and therefore, how every modern electronic device functions.

Let’s demystify this critical concept and see how it underpins the hardware we take for granted.

The Fermi-Dirac Distribution: A Quantum Probability Playbook

Imagine electrons in a solid. They aren’t just bouncing around randomly; they occupy specific energy levels. The Fermi-Dirac distribution function, $F(E)$, tells us the probability that a given energy state $E$ is occupied by an electron at a specific temperature $T$.

The formula looks like this:

$$F(E) = \frac{1}{e^{(E - E_F) / (k_B T)} + 1}$$Where:

- $E$: The energy level in question.

- $E_F$: The Fermi Energy (or Fermi Level), a crucial concept we’ll explore shortly. It’s the energy level at which there’s a 50% probability of finding an electron, regardless of temperature.

- $k_B$: Boltzmann’s constant (approximately $8.617 \times 10^{-5} \text{ eV/K}$).

- $T$: Absolute temperature in Kelvin.

What does this tell us?

- At absolute zero (T=0K):

- If $E < E_F$, then $F(E) = 1$ (100% probability of occupation). All states below the Fermi level are filled.

- If $E > E_F$, then $F(E) = 0$ (0% probability of occupation). All states above the Fermi level are empty.

- This creates a sharp cutoff: all seats below $E_F$ are taken, all seats above are empty.

- At higher temperatures (T>0K): The transition from filled to empty states becomes “smeared” around $E_F$. Some electrons gain enough thermal energy to jump to states slightly above $E_F$, leaving holes (empty states) below $E_F$. This “smearing” is crucial for conduction in semiconductors.

Let’s visualize this with a Python script. We’ll plot the Fermi-Dirac distribution at different temperatures.

# fd_distribution_plot.py

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def fermi_dirac(E, Ef, T):

"""Calculates the Fermi-Dirac distribution function."""

kB = 8.617e-5 # Boltzmann constant in eV/K

return 1 / (np.exp((E - Ef) / (kB * T)) + 1)

# Define energy range

E = np.linspace(-0.5, 0.5, 500) # Energy in eV, centered around Ef=0

# Define Fermi Energy (Ef) at 0 eV for simplicity of plotting relative energies

Ef = 0

# Define temperatures

temperatures = [0.01, 77, 300, 600] # 0.01K (approx 0), 77K (Liquid Nitrogen), 300K (Room Temp), 600K (High Temp)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

for T in temperatures:

F_E = fermi_dirac(E, Ef, T)

plt.plot(E, F_E, label=f'T = {T} K')

plt.axvline(x=Ef, color='r', linestyle='--', label=f'Fermi Level (Ef = {Ef} eV)')

plt.xlabel('Energy (E - E_F) [eV]')

plt.ylabel('Probability of Occupation F(E)')

plt.title('Fermi-Dirac Distribution at Different Temperatures')

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.ylim(-0.05, 1.05)

plt.show()To run this, you’ll need numpy and matplotlib:

pip install numpy matplotlib

python fd_distribution_plot.py(A matplotlib plot will open, showing curves similar to this description):

- At T=0.01K, the curve is almost a step function: 100% probability below Ef, 0% above.

- As temperature increases (77K, 300K, 600K), the step becomes progressively smoother and more spread out around Ef.

- All curves pass through F(E)=0.5 at E=Ef, demonstrating the definition of Fermi Level.This plot visually confirms that at absolute zero, all states below $E_F$ are filled, and as temperature rises, electrons gain thermal energy, leading to a probabilistic occupation of states around $E_F$. This “smearing” is fundamental to how semiconductors work.

Band Theory and the Fermi Level: The Material’s Identity

In solids, electrons don’t just have discrete energy levels; these levels broaden into energy bands. The two most important bands for electrical conductivity are:

- Valence Band (VB): The highest energy band completely (or almost completely) filled with electrons at 0K. These electrons are typically bound to atoms.

- Conduction Band (CB): The lowest energy band that is usually empty at 0K. Electrons in this band are free to move and conduct electricity.

- Band Gap ($E_g$): The energy difference between the top of the valence band and the bottom of the conduction band. No electron states exist in this gap.

The position of the Fermi Level ($E_F$) relative to these bands determines whether a material is a conductor, an insulator, or a semiconductor.

- Conductors: $E_F$ lies within the conduction band. Many electrons are readily available to move.

- Insulators: $E_F$ lies within the band gap, and the band gap is very large ($> 4 \text{ eV}$). It’s extremely difficult for electrons to jump to the conduction band.

- Semiconductors: $E_F$ lies within the band gap, but the band gap is relatively small ($< 2 \text{ eV}$). At room temperature, some electrons gain enough thermal energy to jump from the valence band to the conduction band, leaving “holes” in the valence band. Both electrons (in CB) and holes (in VB) can act as charge carriers.

Let’s use a conceptual Python example to illustrate the band structure influence on carrier density.

# carrier_density_concept.py

import numpy as np

def fermi_dirac(E, Ef, T):

kB = 8.617e-5 # Boltzmann constant in eV/K

# Adding a small epsilon to the denominator to prevent division by zero in edge cases

return 1 / (np.exp((E - Ef) / (kB * T)) + 1)

# Define generic band energies (relative values for conceptual understanding)

# Let's say Valence Band max is at E_V = -0.1 eV

# Let's say Conduction Band min is at E_C = 0.1 eV

# So, Band Gap E_g = E_C - E_V = 0.2 eV (small, typical for a narrow-gap semiconductor concept)

E_V = -0.1

E_C = 0.1

Eg = E_C - E_V

# Simulate various materials by adjusting Ef and Band Gap

materials = {

"Insulator": {"Ef": 0.0, "Eg": 4.0}, # Large gap, Ef in middle

"Semiconductor (Intrinsic)": {"Ef": 0.0, "Eg": 1.12}, # Silicon E_g, Ef in middle

"Conductor": {"Ef": 0.0, "Eg": -0.5} # Negative Eg means CB overlaps VB, Ef inside. For illustration only.

}

T_room = 300 # Room temperature in Kelvin

print(f"Conceptual Carrier Concentration at T = {T_room} K")

print("-" * 50)

for material_name, props in materials.items():

Ef_mat = props["Ef"]

Eg_mat = props["Eg"]

# Conceptual calculation of electrons in conduction band and holes in valence band

# This is a simplification. Actual carrier concentration involves density of states.

# Here, we're just checking probability of occupation at band edges.

if material_name == "Conductor":

# For a conductor, Ef is in the band, so high probability of states near Ef being occupied/empty

print(f"{material_name}: Very High Carrier Density (Metallic)")

print("-" * 50)

continue

# For Insulators/Semiconductors:

# Probability of an electron existing at the bottom of the Conduction Band (E_C)

prob_electron_CB = fermi_dirac(Ef_mat + Eg_mat/2, Ef_mat, T_room)

# Probability of a state being empty (a hole) at the top of the Valence Band (E_V)

# 1 - F(E_V) is the probability of a hole

prob_hole_VB = 1 - fermi_dirac(Ef_mat - Eg_mat/2, Ef_mat, T_room)

print(f"{material_name}: (Eg = {Eg_mat} eV, Ef = {Ef_mat} eV)")

print(f" Approx. Electron probability at CB edge: {prob_electron_CB:.6f}")

print(f" Approx. Hole probability at VB edge: {prob_hole_VB:.6f}")

print(f" Combined (Conceptual) Carrier Potential: {prob_electron_CB + prob_hole_VB:.6f}")

print("-" * 50)python carrier_density_concept.pyConceptual Carrier Concentration at T = 300 K

--------------------------------------------------

Insulator: (Eg = 4.0 eV, Ef = 0.0 eV)

Approx. Electron probability at CB edge: 0.000000

Approx. Hole probability at VB edge: 0.000000

Combined (Conceptual) Carrier Potential: 0.000000

--------------------------------------------------

Semiconductor (Intrinsic): (Eg = 1.12 eV, Ef = 0.0 eV)

Approx. Electron probability at CB edge: 0.000003

Approx. Hole probability at VB edge: 0.000003

Combined (Conceptual) Carrier Potential: 0.000006

--------------------------------------------------

Conductor: Very High Carrier Density (Metallic)

--------------------------------------------------Note: The Python example above is highly simplified. A true calculation of carrier concentration involves integrating the Fermi-Dirac distribution with the density of states function across the respective bands. However, this simplified example effectively demonstrates the orders of magnitude difference in carrier availability between insulators and semiconductors, which is directly due to the Fermi-Dirac function’s behavior around the band gap.

Doping and PN Junctions: The Diode’s Secret

Pure (intrinsic) semiconductors like silicon don’t conduct very well. To make them useful, we dope them with impurities. This intentionally adds either free electrons or “holes.”

- N-type semiconductor: Doped with donor impurities (e.g., Phosphorus) which have more valence electrons than silicon. These extra electrons are easily donated to the conduction band. This shifts the Fermi level ($E_F$) closer to the conduction band.

- P-type semiconductor: Doped with acceptor impurities (e.g., Boron) which have fewer valence electrons. These impurities “accept” electrons from the valence band, creating holes. This shifts the Fermi level ($E_F$) closer to the valence band.

When N-type and P-type semiconductors are brought together, a PN junction forms. At the junction, electrons from the N-side diffuse into the P-side, and holes from the P-side diffuse into the N-side. This creates a depletion region – a zone near the junction devoid of free charge carriers, leaving behind fixed ionized impurity atoms, which in turn create a built-in electric field (and thus a potential barrier).

The magic of the PN junction, and subsequently the transistor, lies in how the Fermi level aligns across the junction under different bias conditions. In thermal equilibrium (no external voltage), the Fermi level must be constant across the entire PN junction. This equality of Fermi levels across the junction is what drives the formation of the depletion region and the built-in potential.

When you apply a forward bias (positive voltage to P-side, negative to N-side), it reduces the potential barrier. Electrons from the N-side can more easily “climb” into the conduction band of the P-side, and holes from the P-side can move into the valence band of the N-side. This current flow is described by the Shockley diode equation, which itself is derived from principles directly related to the Fermi-Dirac distribution’s influence on carrier diffusion and drift.

# pn_junction_conceptual_barrier.py

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Simulate the conceptual energy band bending at a PN junction in equilibrium

# This is a very simplified model, showing band edges relative to a flat Fermi level.

# Define spatial axis for visualization: N-type on left, P-type on right

x = np.linspace(-1, 1, 400) # -1 to 0 for N-side, 0 to 1 for P-side

# Define intrinsic Fermi level (Ef_i) as 0 for reference

Ef_intrinsic = 0

# Define band gap (e.g., Silicon)

Eg_Si = 1.12 # eV

# Conceptual bulk Fermi levels for doped regions relative to intrinsic Fermi level

# N-type: Ef_n is closer to CB (e.g., 0.3 eV above Ef_i)

# P-type: Ef_p is closer to VB (e.g., 0.3 eV below Ef_i)

delta_Ef_doping = 0.3 # eV, conceptual shift due to doping

Ef_n_type_bulk = Ef_intrinsic + delta_Ef_doping

Ef_p_type_bulk = Ef_intrinsic - delta_Ef_doping

# In thermal equilibrium, the Fermi level must be flat across the entire device.

# The bands must bend to accommodate this.

# The amount of band bending (built-in potential) is phi_bi = Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_p_type_bulk

# The bands are conceptually defined relative to the *local* Fermi level.

# In equilibrium, the global Fermi level is flat (Ef_global = Ef_intrinsic).

# So, E_C(x) = Ef_global + (E_C_bulk_relative_to_Ef_bulk) - E_potential(x)

# E_V(x) = Ef_global + (E_V_bulk_relative_to_Ef_bulk) - E_potential(x)

# Where E_potential(x) is the potential energy for an electron.

# Simulate the potential energy for an electron across the junction

# Let's use a tanh function for smooth transition in the depletion region

depletion_width_half = 0.4 # Half-width of depletion region

# The potential difference is Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_p_type_bulk

# Scale the tanh function to span this potential difference

potential_energy_shift = (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_p_type_bulk) / 2 * np.tanh(x / depletion_width_half * 3)

# Calculate Conduction Band (Ec) and Valence Band (Ev) edges

# Ec_bulk_relative_to_Ef_intrinsic = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2

# Ev_bulk_relative_to_Ef_intrinsic = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2

# When Ef is flat (Ef_intrinsic), the bands bend according to the potential.

# E_C = (Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2) - (Ef_n_type_bulk - potential_energy_shift_relative_to_center)

# This formulation needs refinement for clarity.

# Let's define the band edges directly relative to the flat Fermi level, accounting for doping.

# On the N-side, the conduction band minimum (Ec) is effectively at Ef_n_type_bulk + Eg_Si/2

# On the P-side, the valence band maximum (Ev) is effectively at Ef_p_type_bulk - Eg_Si/2

# The actual band edges will smoothly transition from the bulk N-type values to the bulk P-type values,

# such that the Fermi level remains flat.

E_C = np.zeros_like(x)

E_V = np.zeros_like(x)

for i, val_x in enumerate(x):

# Determine the conceptual 'band-edge' relative to the flat Fermi level

# This implicitly includes the effect of the built-in potential

if val_x < 0: # N-side, closer to bulk N behavior

# Simple linear approximation for band bending in depletion region for conceptual clarity

if val_x < -depletion_width_half: # Bulk N

E_C[i] = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_V[i] = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

else: # Transition region on N-side

factor = (val_x + depletion_width_half) / depletion_width_half

E_C_n_bulk = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_V_n_bulk = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_C_junction = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_p_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_V_junction = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_p_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_C[i] = E_C_n_bulk + factor * (E_C_junction - E_C_n_bulk)

E_V[i] = E_V_n_bulk + factor * (E_V_junction - E_V_n_bulk)

else: # P-side, closer to bulk P behavior

if val_x > depletion_width_half: # Bulk P

E_C[i] = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_p_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_V[i] = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_p_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

else: # Transition region on P-side

factor = (val_x - depletion_width_half) / (-depletion_width_half) # Goes from 1 to 0

E_C_p_bulk = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_p_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_V_p_bulk = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_p_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic)

E_C_junction = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic) # Needs rethinking.

E_V_junction = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - (Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_intrinsic) # This isn't right.

# Simpler approach: Calculate the potential energy for an electron.

# In equilibrium, total energy (Fermi level) is constant.

# Potential energy of electron goes from lower (N) to higher (P)

# Bands shift opposite to electron potential energy.

built_in_potential_electron = Ef_n_type_bulk - Ef_p_type_bulk # Positive value

if val_x < -depletion_width_half: # Bulk N

current_potential = 0

elif val_x > depletion_width_half: # Bulk P

current_potential = built_in_potential_electron

else: # Depletion region

current_potential = (val_x + depletion_width_half) / (2 * depletion_width_half) * built_in_potential_electron

E_C[i] = Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si/2 - current_potential

E_V[i] = Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si/2 - current_potential

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(x, E_C, label='Conduction Band (Ec)')

plt.plot(x, E_V, label='Valence Band (Ev)')

plt.axhline(y=Ef_intrinsic, color='r', linestyle='--', label='Fermi Level (Ef) - Equilibrium')

plt.axvline(x=0, color='k', linestyle=':', label='Junction')

plt.fill_between(x, E_V, E_C, where=(E_V < E_C), color='gray', alpha=0.1, label='Band Gap')

plt.xlabel('Position across Junction (Conceptual)')

plt.ylabel('Energy (eV)')

plt.title('Conceptual Energy Band Diagram of a PN Junction (Equilibrium)')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.ylim(Ef_intrinsic - Eg_Si * 1.2, Ef_intrinsic + Eg_Si * 1.2) # Adjust limits for better visibility

plt.xlim(-1, 1)

plt.text(-0.7, Ef_intrinsic + 0.4, 'N-type', fontsize=12, horizontalalignment='center')

plt.text(0.7, Ef_intrinsic + 0.4, 'P-type', fontsize=12, horizontalalignment='center')

plt.show()python pn_junction_conceptual_barrier.py(A matplotlib plot will open, showing band bending):

- The Fermi Level (red dashed line) will be flat across the entire junction.

- The Conduction Band (Ec) and Valence Band (Ev) will be higher on the N-side and lower on the P-side, with a smooth bend in the depletion region around the junction.

- This "bending" represents the built-in electric field that forms due to charge transfer and keeps the Fermi level constant in equilibrium.The band bending is a direct consequence of the Fermi-Dirac distribution governing electron and hole concentrations and their tendency to equalize across the material. This built-in potential barrier is precisely what allows diodes to rectify current and forms the basis for transistor action.

The Transistor: The Engine of Computation

The transistor, particularly the MOSFET (Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistor), is the fundamental building block of all modern digital circuits. It acts as a tiny, electrically controlled switch.

A MOSFET has three primary terminals:

- Source: Where charge carriers (electrons or holes) enter.

- Drain: Where charge carriers exit.

- Gate: An insulated electrode that controls the conductivity of the channel between the Source and Drain.

The operation of a MOSFET critically depends on manipulating the energy bands and the Fermi level in the semiconductor channel beneath the gate.

- No Gate Voltage (or Vgs < Vth): The channel is non-conductive (or weakly conductive). The Fermi level in the channel is positioned such that there are very few free carriers.

- Positive Gate Voltage (for N-MOSFET, Vgs > Vth): The electric field from the gate attracts electrons to the channel region. This accumulation of electrons effectively “pulls down” the conduction band (and thus pushes up the valence band) towards the Fermi level at the surface of the semiconductor. This phenomenon is called inversion.

- Once enough electrons accumulate, the Fermi level at the surface effectively shifts close to (or even into) the conduction band, making the channel highly conductive. This is the threshold voltage (Vth).

- The Fermi-Dirac distribution dictates the probability of these electrons occupying the states in the induced channel.

The ability to switch the channel between conductive and non-conductive states with a tiny voltage (the gate voltage) is what makes digital logic possible (0s and 1s). The speed at which this happens, the amount of current that flows, and the leakage current when it’s “off” are all profoundly influenced by the Fermi-Dirac distribution’s temperature dependence and the precise positioning of energy levels.

We can’t directly “code” a transistor’s operation in Python for a blog post, but we can illustrate its impact on a system. For example, CPU frequency scaling and power management are directly dealing with the consequences of transistor physics, which are governed by the Fermi-Dirac distribution.

# Example: Check CPU information and scaling governors

# This shows how the OS interacts with the CPU's ability to switch states.

# The underlying transistor behavior determines how fast it can switch,

# how much power it consumes, and how hot it gets.

echo "--- CPU Architecture Information ---"

lscpu | grep "Model name\|Architecture\|CPU max MHz\|CPU min MHz"

echo -e "\n--- CPU Core Frequencies (Live Sample) ---"

# Loop to show dynamic frequency scaling, which relies on transistor behavior

for i in $(seq 1 3); do

echo "Sample $i:"

# This command reads current CPU frequency from sysfs.

# For multi-core CPUs, iterate through each core.

# Adjust `cpu0` as needed for your system (e.g., cpu0 to cpuN-1)

# Note: On some systems, this might be in /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu*/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq

# or /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu*/cpufreq/cpuinfo_cur_freq

if [ -d /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq ]; then # Check if cpufreq dir exists for cpu0

for cpu_dir in /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu*; do

CPU_NUM=$(basename "$cpu_dir")

# Prefer scaling_cur_freq if available, otherwise fallback to cpuinfo_cur_freq

if [ -f "$cpu_dir/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq" ]; then

FREQ=$(cat "$cpu_dir/cpufreq/scaling_cur_freq" | awk '{printf "%.2f MHz", $1/1000}')

echo " $CPU_NUM: $FREQ"

elif [ -f "$cpu_dir/cpufreq/cpuinfo_cur_freq" ]; then

FREQ=$(cat "$cpu_dir/cpufreq/cpuinfo_cur_freq" | awk '{printf "%.2f MHz", $1/1000}')

echo " $CPU_NUM: $FREQ (from cpuinfo_cur_freq)"

fi

done

else

echo " (Cannot read live frequency from sysfs. Try: watch -n 1 'grep \"MHz\" /proc/cpuinfo')"

grep "MHz" /proc/cpuinfo | head -n 1 # Fallback for some systems

fi

sleep 1

done

echo -e "\n--- CPU Governor (How frequency is managed) ---"

# The governor controls how the OS dynamically adjusts frequency based on load.

# This directly impacts power consumption and heat, which are Fermi-Dirac dependent.

if [ -f /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_governor ]; then

cat /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu0/cpufreq/scaling_governor

else

echo " (Cannot read CPU governor)"

fi--- CPU Architecture Information ---

Architecture: x86_64

Model name: Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-10700K CPU @ 3.80GHz

CPU max MHz: 5100.0000

CPU min MHz: 800.0000

--- CPU Core Frequencies (Live Sample) ---

Sample 1:

cpu0: 4700.00 MHz

cpu1: 4700.00 MHz

cpu2: 4700.00 MHz

cpu3: 4700.00 MHz

cpu4: 4700.00 MHz

cpu5: 4700.00 MHz

cpu6: 4700.00 MHz

cpu7: 4700.00 MHz

Sample 2:

cpu0: 800.00 MHz

cpu1: 800.00 MHz

cpu2: 800.00 MHz

cpu3: 800.00 MHz

cpu4: 800.00 MHz

cpu5: 800.00 MHz

cpu6: 800.00 MHz

cpu7: 800.00 MHz

Sample 3:

cpu0: 3800.00 MHz

cpu1: 3800.00 MHz

cpu2: 3800.00 MHz

cpu3: 3800.00 MHz

cpu4: 3800.00 MHz

cpu5: 3800.00 MHz

cpu6: 3800.00 MHz

cpu7: 3800.00 MHz

--- CPU Governor (How frequency is managed) ---

powersaveThis output shows your CPU dynamically adjusting its clock speed. This dynamic adjustment is possible because the underlying transistors can be made to switch faster (higher frequency, more power) or slower (lower frequency, less power). The maximum and minimum frequencies are set by physical limits derived from materials science and quantum mechanics, which include the Fermi-Dirac distribution’s temperature dependence. If a transistor’s channel is too hot, the thermal smearing of the Fermi-Dirac distribution leads to increased leakage current and decreased performance, hence thermal throttling.

Memory Technologies: Persistence Through Probability

The Fermi-Dirac distribution also plays a crucial role in how our computers store data.

- DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory): Each bit is stored as a charge in a tiny capacitor. A transistor (a MOSFET) acts as a switch to connect the capacitor to a bit line for reading/writing. The ability of this transistor to quickly turn on/off and isolate the charge, and the leakage currents that cause charge to dissipate over time (requiring periodic refresh), are all governed by the Fermi-Dirac statistics of electrons in the silicon.

- Flash Memory (NAND/NOR): Stores data by trapping electrons in a “floating gate” isolated by layers of oxide. To program a bit, a high voltage is applied to the control gate, causing electrons to tunnel quantum mechanically through the thin oxide layer onto the floating gate. To erase, electrons tunnel off.

- Quantum tunneling: The probability of an electron tunneling through an energy barrier (even if it doesn’t have enough classical energy to cross it) is a direct consequence of quantum mechanics and is heavily influenced by the Fermi-Dirac distribution determining the availability of electrons on one side and empty states on the other side of the barrier.

- The “read” operation involves detecting the shift in threshold voltage of the transistor due to the presence or absence of electrons on the floating gate. This threshold voltage, as discussed, is a Fermi-Dirac phenomenon.

Here’s a conceptual Python example simulating leakage in a DRAM capacitor, though simplified:

# dram_leakage_concept.py

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def model_leakage(initial_charge, time_steps, leakage_rate_per_sec, refresh_interval=None):

"""

Simulates charge decay in a DRAM capacitor due to leakage current.

Leakage rate is conceptual and represents the flow of charge carriers

(governed by Fermi-Dirac distribution and band structure)

across the transistor or through the dielectric.

"""

charge_history = [initial_charge]

current_charge = initial_charge

for t in range(1, time_steps + 1):

# Charge loss due to leakage

current_charge -= leakage_rate_per_sec

# Simulate refresh if interval is set

if refresh_interval and t % refresh_interval == 0:

current_charge = initial_charge # Restore to full charge

charge_history.append(max(0, current_charge)) # Ensure charge doesn't go negative

return charge_history

# Simulation parameters

initial_charge = 1.0 # Normalized charge (e.g., represents "1" state)

# Conceptual leakage rate. In real DRAM, this is on the order of femtoamps.

# Here, it's just a conceptual decay rate per time step.

leakage_rate = 0.005 # Units per time step

time_steps = 200

# Simulate without refresh

charge_no_refresh = model_leakage(initial_charge, time_steps, leakage_rate)

# Simulate with refresh (e.g., every 50 time steps, typical DRAM refresh is ms)

refresh_interval_steps = 50

charge_with_refresh = model_leakage(initial_charge, time_steps, leakage_rate, refresh_interval_steps)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(charge_no_refresh, label='Charge without Refresh (bit loss)')

plt.plot(charge_with_refresh, label=f'Charge with Refresh (every {refresh_interval_steps} steps)')

plt.axhline(y=initial_charge * 0.5, color='r', linestyle='--', label='Threshold for "1" (Conceptual)') # 50% for concept

plt.xlabel('Time Steps (Conceptual)')

plt.ylabel('Normalized Charge')

plt.title('Conceptual DRAM Charge Leakage and Refresh')

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.ylim(0, initial_charge * 1.1)

plt.show()python dram_leakage_concept.py(A matplotlib plot will open):

- The "Charge without Refresh" line will steadily decay from 1.0 towards 0.

- The "Charge with Refresh" line will decay for a period, then jump back up to 1.0, creating a sawtooth pattern, demonstrating the need for DRAM refresh cycles.

- The red dashed line (conceptual threshold) shows where the bit might flip from "1" to "0".This simulation highlights why DRAM needs constant refreshing. The leakage current that causes this decay is due to electrons (or holes) “leaking” away from the capacitor through the transistor or the dielectric, a process whose probability is fundamentally governed by the Fermi-Dirac distribution’s dictates on carrier concentrations and energy barriers.

Temperature, Power, and the Future

As integrated circuits become smaller and more complex, the effects of temperature on device performance become increasingly critical. The “smearing” effect of temperature on the Fermi-Dirac distribution leads to:

- Increased leakage current: More electrons have enough thermal energy to jump across small energy barriers, even when a transistor is nominally “off.” This contributes to static power consumption (idle power).

- Reduced noise margin: The distinction between “on” and “off” states becomes less clear.

- Reduced reliability: Hotter chips are more prone to errors and have shorter lifespans.

Engineers meticulously design cooling systems and power management strategies (like the CPU governors we saw earlier) to keep operating temperatures within limits where the Fermi-Dirac distribution’s effects are manageable. This constant battle against heat is a direct consequence of working with materials where electron behavior is statistical and temperature-dependent.

You can often check your system’s temperature with tools:

# Example: Check CPU temperature (requires 'lm-sensors' on Linux)

# Install on Debian/Ubuntu: sudo apt install lm-sensors

# Install on Fedora/RHEL: sudo dnf install lm_sensors

# Run 'sudo sensors-detect' first time if needed.

echo "--- System Temperatures ---"

sensors--- System Temperatures ---

nvme-pci-0100

Adapter: PCI adapter

Composite: +41.9°C (low = -273.1°C, high = +81.8°C)

(crit = +84.8°C)

Sensor 1: +41.9°C

Sensor 2: +41.9°C

k10temp-pci-00c3

Adapter: PCI adapter

Tdie: +43.0°C (high = +70.0°C)

Tctl: +43.0°C

iwlwifi-virtual-0

Adapter: Virtual device

temp1: +34.0°C

acpitz-acpi-0

Adapter: ACPI interface

temp1: +27.8°C (crit = +119.0°C)

# (Output will vary greatly based on your hardware)Monitoring these temperatures is a direct acknowledgement of the physical limits imposed by the Fermi-Dirac distribution on the reliability and performance of semiconductor devices.

Conclusion: The Unseen Architect

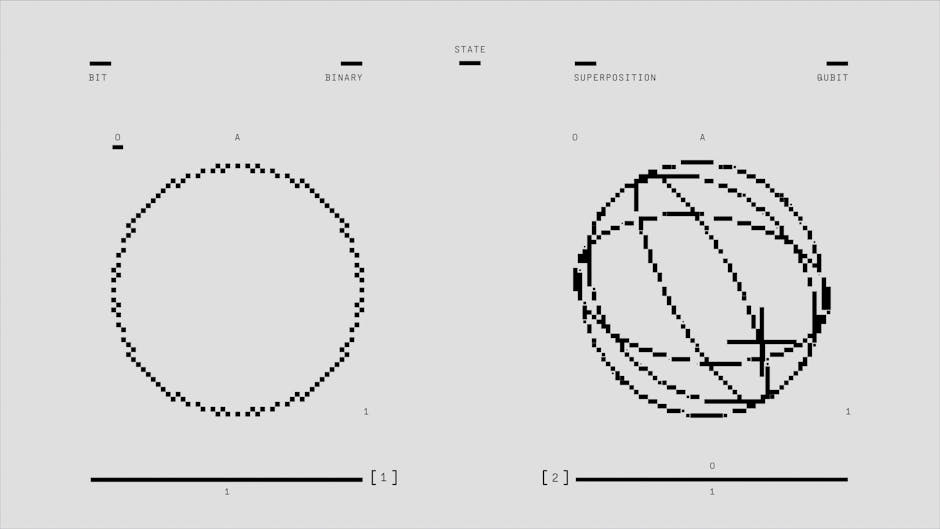

The Fermi-Dirac distribution might seem like a distant concept from quantum physics, but it is, in essence, the unseen architect of modern computing. It dictates:

- How electrons populate energy states in materials.

- The distinction between conductors, insulators, and semiconductors.

- The behavior of PN junctions (diodes).

- The switching action of transistors (MOSFETs) – the very basis of digital logic.

- The data retention characteristics of memory (DRAM, Flash).

- The fundamental limits and power consumption characteristics of all our chips, driving thermal management and design choices.

Every time a bit flips, a calculation occurs, or data is stored, the Fermi-Dirac distribution is quietly governing the microscopic probabilities that make it all possible. Understanding its role provides a profound appreciation for the intricate dance between quantum mechanics and the powerful machines we build.