How Quantum Tunneling Makes SSDs Work (And Why They Wear Out)

You plug in an SSD, format it, and it just works. Fast. Reliable. Silent. But have you ever stopped to think about the insane physics happening at the heart of your data storage? Beneath the sleek aluminum casing and the sophisticated controller, your SSD is performing a feat of quantum mechanics every time it stores a bit of data.

Yes, seriously. We’re talking quantum tunneling.

This isn’t some abstract theoretical concept; it’s the fundamental principle that allows the NAND flash memory inside your SSD to function. Understanding it not only demystifies how these devices work but also sheds light on their limitations, like why they have a finite lifespan.

Let’s dive in.

The Quantum Leap: What is Tunneling?

Imagine a ball rolling towards a hill. Classically, if the ball doesn’t have enough kinetic energy to get over the hill, it’ll just roll back down. Simple physics.

Now, imagine an electron approaching an energy barrier – a region where it classically shouldn’t be able to go because it lacks the required energy. In the quantum world, things get weird. Instead of being completely blocked, there’s a probability that the electron can simply appear on the other side of the barrier, without ever “going over” it. It’s like the ball suddenly appearing on the other side of the hill, even though it didn’t have enough energy to roll over.

This phenomenon is called quantum tunneling.

It’s not magic, but a consequence of the wave-particle duality of matter and the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics. Particles aren’t just tiny points; they have wave-like properties. Their position isn’t perfectly defined; instead, there’s a probability distribution for where they might be found. If the barrier is thin enough, this probability distribution can “leak” through to the other side.

The key factors for tunneling are:

- Barrier Thickness: The thinner the barrier, the higher the probability of tunneling.

- Particle Mass: Lighter particles (like electrons) tunnel more easily.

- Energy Difference: The smaller the energy difference between the particle and the barrier, the easier it is.

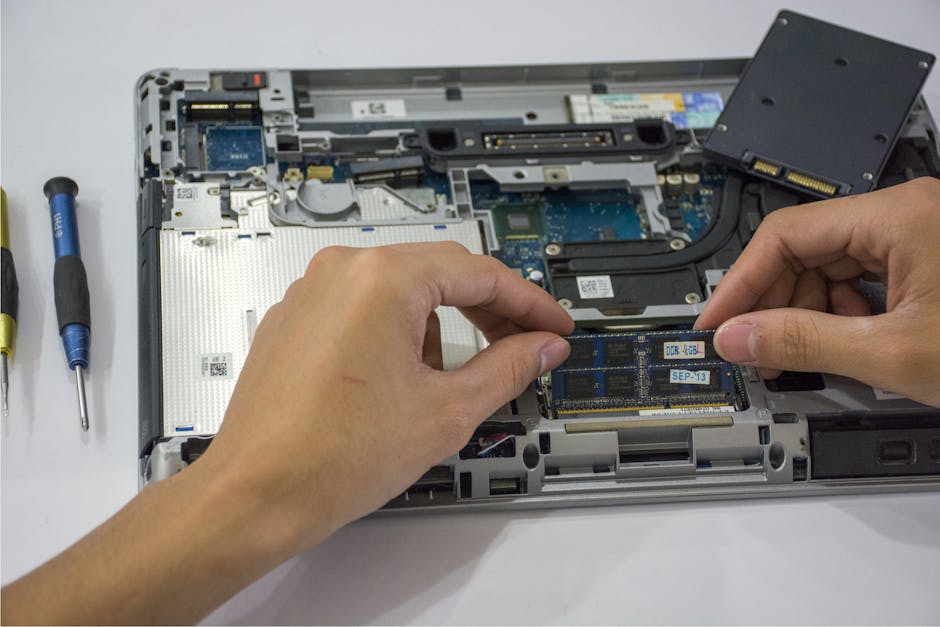

Anatomy of an SSD: The NAND Flash Cell

Before we connect tunneling to SSDs, let’s understand the basic building block of an SSD: the NAND flash cell. Most modern SSDs use variations of this (MLC, TLC, QLC), but the core principle is the same.

Each NAND cell is essentially a specialized transistor designed to store an electrical charge. It consists of:

- Control Gate (CG): This is like the standard gate of a transistor, used to apply voltage and control the flow of electrons.

- Floating Gate (FG): This is the crucial part. It’s a layer of conductive material (often polysilicon) that is electrically isolated from everything around it by insulating layers. Once electrons are trapped here, they stay trapped.

- Tunnel Oxide (TO): A very thin insulating layer located between the floating gate and the channel (where electrons flow from source to drain). This is where quantum tunneling happens.

- Inter-poly Dielectric (IPD): Another insulating layer, between the control gate and the floating gate.

- Source and Drain: The ends of the channel where electrons enter and exit the transistor.

How it stores a bit:

The presence or absence of electrons on the floating gate determines whether a cell stores a 0 or a 1.

- No electrons (or few): Cell is in one state (e.g.,

1). - Electrons trapped: Cell is in the other state (e.g.,

0).

The Magic Touch: Tunneling in Action

Now, let’s bring it all together. Quantum tunneling is precisely how electrons get onto and off of the floating gate.

Writing Data (Programming a Cell)

To store a 0 (by trapping electrons), a high positive voltage is applied to the Control Gate. This creates a strong electric field across the Tunnel Oxide layer. Because the Tunnel Oxide is incredibly thin (just a few nanometers thick!), electrons in the channel (from the source) can quantum tunnel through this insulating barrier and become trapped on the Floating Gate.

This specific type of tunneling is often called Fowler-Nordheim tunneling.

Think of it: the electrons don’t climb over the insulation; they tunnel right through it. This is a non-destructive, controlled leak facilitated by the strong electric field and the unbelievably thin barrier.

Erasing Data

To erase a cell (remove electrons, typically to set it to 1), a high negative voltage is applied to the Control Gate (or a high positive voltage to the substrate, depending on the architecture). This creates an electric field in the opposite direction, pulling the trapped electrons off the Floating Gate, back through the Tunnel Oxide, and into the channel/substrate. This is also a form of quantum tunneling.

Reading Data

Reading data does not involve tunneling. Instead, a specific voltage is applied to the Control Gate, and the electrical conductivity of the channel is measured.

- If electrons are trapped on the Floating Gate, their negative charge affects the electric field, making it harder for current to flow through the channel (higher threshold voltage).

- If no electrons are trapped, current flows more easily (lower threshold voltage).

The SSD controller reads this difference in conductivity to determine if the cell stores a

0or a1.

The Unvarnished Truth: Trade-offs & Limitations

This ingenious use of quantum tunneling comes with a cost, and it’s why your SSD isn’t immortal.

-

Endurance (Program/Erase Cycles): Every time electrons tunnel through the Tunnel Oxide, they impart a tiny amount of energy to the silicon dioxide lattice. Over thousands of cycles, this can cause microscopic damage to the insulating layer. Think of it like chipping away at a wall. Eventually, the tunnel oxide degrades, becoming “leaky” or completely failing. This limits the number of Program/Erase (P/E) cycles a NAND cell can endure before it can no longer reliably store or release electrons. This is why SSDs have a finite lifespan, measured in TBW (Terabytes Written).

-

Data Retention: Even when no voltage is applied, there’s a small but non-zero probability that trapped electrons can quantum tunnel off the Floating Gate over time, especially at elevated temperatures. This leakage leads to data degradation and eventually data loss if not refreshed. This is why SSDs have a data retention specification (e.g., 1 year at 30°C for unpowered drive).

-

Scaling Challenges: To increase SSD capacity and reduce cost, manufacturers try to shrink NAND cells. This means making the Tunnel Oxide even thinner. While thinner barriers make tunneling easier (good for lower voltage operation), they also increase the probability of unwanted tunneling (data leakage) and accelerate wear. This tightrope walk is a major engineering challenge and drives the move towards MLC, TLC, QLC, and now PLC (5 bits per cell), which pack more bits into each cell but typically come with lower endurance and retention due to finer voltage distinctions and increased tunneling sensitivity.

Developer’s Toolkit: Working with SSDs

Understanding the underlying physics helps you make better decisions as a developer.

1. Checking SSD Health with smartctl

Since wear is an inherent property of SSDs, monitoring their health is crucial. On Linux, smartctl from the smartmontools package is your best friend. It queries the drive’s S.M.A.R.T. (Self-Monitoring, Analysis and Reporting Technology) attributes.

Install smartmontools (if not already present):

sudo apt update

sudo apt install smartmontoolsCheck a specific drive’s health:

First, identify your SSD device name (e.g., /dev/sda, /dev/nvme0n1).

lsblkNAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sda 8:0 0 1.8T 0 disk

└─sda1 8:1 0 1.8T 0 part /data

nvme0n1 259:0 0 476.9G 0 disk

├─nvme0n1p1 259:1 0 512M 0 part /boot/efi

├─nvme0n1p2 259:2 0 1G 0 part /boot

└─nvme0n1p3 259:3 0 475.4G 0 part /In this example, /dev/nvme0n1 is an NVMe SSD and /dev/sda is a SATA SSD. Let’s check the NVMe one.

sudo smartctl -a /dev/nvme0n1smartctl 7.2 2020-12-30 r5155 [x86_64-linux-5.15.0-86-generic] (local build)

Copyright (C) 2002-20, Bruce Allen, Christian Franke, www.smartmontools.org

=== START OF SMART DATA SECTION ===

SMART overall health self-assessment test result: PASSED

SMART/Health Information (NVMe Log 0x02)

Critical Warning: 0x00

Temperature: 35 Celsius

Available Spare: 100%

Available Spare Threshold: 10%

Percentage Used: 1% <-- This is crucial!

Data Units Read: 4,567,890 [2.33 TB]

Data Units Written: 3,456,789 [1.77 TB]

Host Read Commands: 987,654,321

Host Write Commands: 123,456,789

Controller Busy Time: 0

Power Cycles: 1234

Power On Hours: 5678

Unsafe Shutdowns: 12

Media Errors: 0

Number of Error Information Log Entries: 0

Error Information (NVMe Log 0x01, 1 of 1 entries)

No Errors LoggedKey metrics to watch for:

Percentage Used: This is an estimated indicator of remaining drive life, based on TBW. A value of 1% means it has consumed 1% of its rated write endurance.Available Spare: Percentage of the remaining spare block capacity available. As cells wear out, the SSD controller uses these spare blocks. When this drops below theAvailable Spare Threshold, it indicates significant wear.

2. Enabling TRIM

TRIM is a command that allows the operating system to inform the SSD controller which data blocks are no longer in use (i.e., have been deleted by the user). This allows the SSD to internally erase these blocks when idle, preventing performance degradation and extending lifespan by facilitating more efficient wear leveling.

Modern Linux distributions typically enable TRIM automatically via fstrim.timer.

Check if TRIM timer is active:

systemctl status fstrim.timer● fstrim.timer - Discard unused blocks once a week

Loaded: loaded (/lib/systemd/system/fstrim.timer; enabled; vendor preset: enabled)

Active: active (waiting) since Fri 2023-10-27 08:30:00 UTC; 2h ago

Trigger: Mon 2023-10-30 00:00:00 UTC; 2 days left

Docs: man:fstrimIf it’s active (waiting) and enabled, you’re good to go. It runs weekly by default.

Manually run TRIM (if needed, or for testing):

sudo fstrim -av/boot/efi: 139.7 MiB (146401280 bytes) trimmed

/boot: 312.4 MiB (327598080 bytes) trimmed

/: 113.8 GiB (122214656000 bytes) trimmedThis command reports how much data was trimmed on each mounted filesystem.

3. Understanding Wear Leveling and Over-provisioning

Because of the limited P/E cycles due to quantum tunneling, SSD controllers employ sophisticated techniques:

- Wear Leveling: The controller actively distributes writes evenly across all NAND cells to prevent specific cells from wearing out prematurely. This ensures the entire drive reaches its endurance limit more uniformly.

- Over-provisioning: SSDs often have more physical NAND capacity than advertised (e.g., a 256GB SSD might have 280GB of raw NAND). This extra capacity acts as a pool of spare blocks for wear leveling, garbage collection, and bad block management. It directly extends the useful life of the SSD. This is why enterprise SSDs often have significantly higher over-provisioning.

While you can’t directly configure these (they’re handled by the controller), understanding them reinforces why smartctl’s “Percentage Used” is a crucial metric, as it reflects the controller’s internal management of wear.

4. The MLC/TLC/QLC Trade-off

The number of bits stored per cell (MLC = Multi-Level Cell, 2 bits; TLC = Triple-Level Cell, 3 bits; QLC = Quad-Level Cell, 4 bits) directly impacts endurance and cost:

- MLC: Stores 2 bits per cell, requiring 4 distinct voltage levels. Less precise, higher endurance.

- TLC: Stores 3 bits per cell, requiring 8 distinct voltage levels. More precise, lower endurance than MLC, but higher capacity and lower cost.

- QLC: Stores 4 bits per cell, requiring 16 distinct voltage levels. Even more precise, lowest endurance, but highest capacity and lowest cost.

As you pack more bits, the voltage differences between states become smaller, making the cell more susceptible to noise and, critically, data leakage due to quantum tunneling. This is why QLC drives typically have the lowest endurance and shortest data retention – the small charge differences are more easily blurred by stray electrons tunneling on or off the floating gate over time.

Conclusion

Your SSD is a marvel of engineering that leverages the “weirdness” of quantum mechanics to store your precious data. Quantum tunneling, the very phenomenon that allows electrons to breach seemingly impenetrable barriers, is the core mechanism for writing and erasing data in NAND flash memory.

But this quantum elegance comes with an expiry date. The constant tunneling, though controlled, gradually degrades the insulating layers, leading to the finite endurance and data retention limitations we see in SSDs.

As developers, while we don’t directly manipulate electrons in a floating gate, understanding these fundamental principles gives us a deeper appreciation for the tools we use daily. It also empowers us to make informed decisions about drive selection, monitor health, and ensure our data remains safe for as long as possible within the quantum confines of our storage devices.

So next time you git commit or docker build, spare a thought for the tiny electrons doing their quantum dance inside your drive, making it all possible.