How Quantum Logic Gates Differ from Classical Ones

As developers, we build on layers of abstraction, and at the very bottom of our digital world lies the logic gate. These fundamental building blocks manipulate information, transforming inputs into outputs. For decades, classical logic gates have powered every piece of silicon we interact with. But now, a new paradigm is emerging: quantum computing, which operates with an entirely different set of rules and, consequently, a different set of logic gates.

This post will peel back the layers, comparing classical and quantum logic gates side-by-side. We’ll explore their fundamental differences, from how they represent information to how they process it, all backed by runnable code examples.

Classical Logic Gates: The Deterministic Foundation

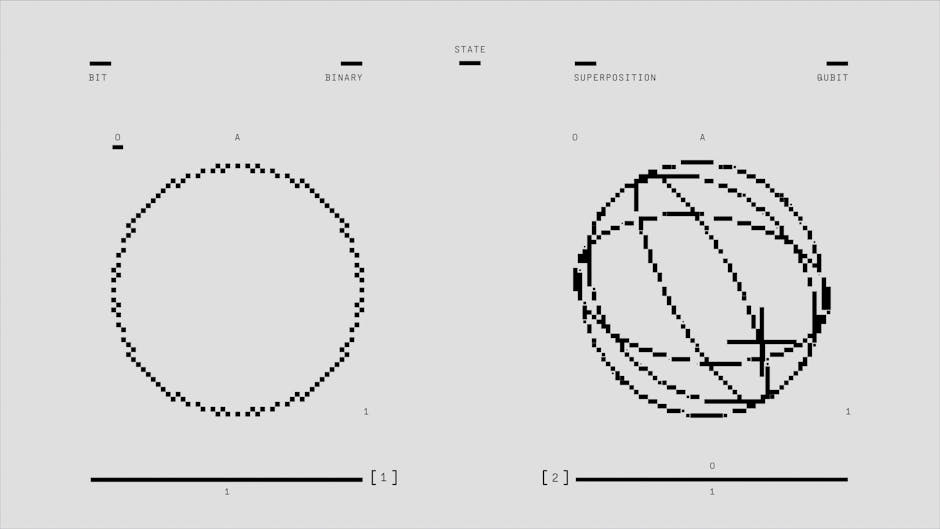

At its heart, classical computing relies on the bit, which can be in one of two definite states: 0 (off/false) or 1 (on/true). Classical logic gates perform operations on these bits based on Boolean algebra. They are:

- Deterministic: Given the same input, you always get the same output.

- Irreversible (often): Information can be lost. For example, knowing the output of an

ANDgate (e.g.,0) doesn’t tell you the original inputs. - Physical: Implemented using transistors that represent voltage levels.

Let’s look at a couple of common classical gates: the NOT gate and the AND gate.

The NOT Gate (Classical)

The NOT gate (also known as an inverter) takes a single bit as input and flips its value: 0 becomes 1, and 1 becomes 0.

# classical_not_gate.py

def classical_not(bit: int) -> int:

"""

Simulates a classical NOT gate.

Input must be 0 or 1.

"""

if bit == 0:

return 1

elif bit == 1:

return 0

else:

raise ValueError("Input must be 0 or 1")

print(f"NOT 0: {classical_not(0)}")

print(f"NOT 1: {classical_not(1)}")Let’s run this simple Python script:

python classical_not_gate.pyNOT 0: 1

NOT 1: 0As expected, it’s a straightforward flip.

The AND Gate (Classical)

The AND gate takes two bits as input and outputs 1 only if both inputs are 1. Otherwise, it outputs 0. This gate demonstrates information loss. If the output is 0, you don’t know if the inputs were (0,0), (0,1), or (1,0).

# classical_and_gate.py

def classical_and(bit_a: int, bit_b: int) -> int:

"""

Simulates a classical AND gate.

Inputs must be 0 or 1.

"""

if bit_a == 1 and bit_b == 1:

return 1

else:

return 0

print(f"0 AND 0: {classical_and(0, 0)}")

print(f"0 AND 1: {classical_and(0, 1)}")

print(f"1 AND 0: {classical_and(1, 0)}")

print(f"1 AND 1: {classical_and(1, 1)}")Running the AND gate simulation:

python classical_and_gate.py0 AND 0: 0

0 AND 1: 0

1 AND 0: 0

1 AND 1: 1Quantum Logic Gates: Probabilistic and Reversible

Quantum logic gates operate on qubits, which are fundamentally different from classical bits. A qubit can be:

- In the state

|0⟩(pronounced “ket 0”) - In the state

|1⟩(pronounced “ket 1”) - In a superposition of

|0⟩and|1⟩simultaneously. This is often represented asα|0⟩ + β|1⟩, where α and β are complex probability amplitudes, and|α|^2 + |β|^2 = 1. This means there’s a|α|^2probability of measuring|0⟩and|β|^2probability of measuring|1⟩.

The differences ripple through to how gates work:

- Probabilistic: Upon measurement, a qubit in superposition “collapses” to either

|0⟩or|1⟩with a certain probability. Quantum gates manipulate these probabilities and the phase relationships between states. - Reversible: All quantum gates are fundamentally reversible. They are represented by unitary matrices, which means information is never lost. This is a critical property for quantum algorithms.

- Entanglement: Quantum gates can create and manipulate entanglement, a uniquely quantum phenomenon where two or more qubits become linked, such that the state of one instantly influences the state of the others, regardless of distance.

- No-Cloning Theorem: It’s impossible to create an identical copy of an arbitrary unknown quantum state. This has profound implications for how information is processed and secured in quantum systems.

We’ll use Qiskit for our quantum examples, a popular open-source SDK for working with quantum computers at the level of circuits, pulses, and algorithms. Make sure you have it installed: pip install qiskit.

The Hadamard Gate (H)

The Hadamard gate is one of the most fundamental quantum gates. When applied to a |0⟩ or |1⟩ state, it creates an equal superposition.

H|0⟩results in(1/√2)|0⟩ + (1/√2)|1⟩(equal probability of0or1).H|1⟩results in(1/√2)|0⟩ - (1/√2)|1⟩(equal probability of0or1, but with a phase difference).

Let’s see this in action. We’ll start with a qubit in the |0⟩ state, apply a Hadamard gate, and then measure it multiple times to see the probabilistic outcome.

# quantum_hadamard.py

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, transpile

from qiskit_aer import AerSimulator

from qiskit.visualization import plot_histogram

# Use the AerSimulator for local simulation

simulator = AerSimulator()

# Create a Quantum Circuit with one qubit and one classical bit

circuit = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

# Initialize the qubit in |0⟩ state (default for Qiskit)

# Apply Hadamard gate to qubit 0

circuit.h(0)

# Measure qubit 0 and map it to classical bit 0

circuit.measure(0, 0)

# Compile the circuit for the simulator

compiled_circuit = transpile(circuit, simulator)

# Run the simulation 1024 times

job = simulator.run(compiled_circuit, shots=1024)

# Grab results from the job

result = job.result()

# Returns counts

counts = result.get_counts(compiled_circuit)

print(f"Counts after Hadamard and measurement (1024 shots): {counts}")

# You can also visualize the circuit

# print(circuit.draw()) # uncomment to see ASCII circuit drawingLet’s run this. The output will vary slightly due to the probabilistic nature, but it should be close to 50/50 for 0 and 1.

python quantum_hadamard.pyCounts after Hadamard and measurement (1024 shots): {'1': 515, '0': 509}Note: The plot_histogram function would typically generate a graphical histogram, which is excellent for visualizing probabilities. For a CLI example, we’re just printing the raw counts.

The Pauli-X Gate (Quantum NOT)

The Pauli-X gate is the quantum equivalent of the classical NOT gate. It flips the state of a qubit:

X|0⟩becomes|1⟩X|1⟩becomes|0⟩- If applied to a superposition

α|0⟩ + β|1⟩, it transforms it toβ|0⟩ + α|1⟩.

# quantum_pauli_x.py

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, transpile

from qiskit_aer import AerSimulator

simulator = AerSimulator()

# Test X on |0⟩

circuit_0 = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

circuit_0.x(0) # Apply Pauli-X to qubit 0

circuit_0.measure(0, 0)

job_0 = simulator.run(transpile(circuit_0, simulator), shots=100)

counts_0 = job_0.result().get_counts(circuit_0)

print(f"X on |0⟩ (100 shots): {counts_0}")

# Test X on |1⟩

# To prepare |1⟩, we first apply X to |0⟩

circuit_1 = QuantumCircuit(1, 1)

circuit_1.x(0) # Prepare |1⟩ from |0⟩

circuit_1.x(0) # Apply Pauli-X again (now X on |1⟩)

circuit_1.measure(0, 0)

job_1 = simulator.run(transpile(circuit_1, simulator), shots=100)

counts_1 = job_1.result().get_counts(circuit_1)

print(f"X on |1⟩ (100 shots): {counts_1}")python quantum_pauli_x.pyX on |0⟩ (100 shots): {'1': 100}

X on |1⟩ (100 shots): {'0': 100}This confirms the deterministic nature of Pauli-X on basis states (|0⟩ or |1⟩).

The Controlled-NOT Gate (CNOT or CX)

The CNOT gate is a two-qubit gate. It’s often called the “workhorse” of quantum computing because it’s crucial for creating entanglement.

- It has a control qubit and a target qubit.

- If the control qubit is

|0⟩, the target qubit remains unchanged. - If the control qubit is

|1⟩, the target qubit’s state is flipped (like a Pauli-X).

The magic happens when the control qubit is in a superposition. Consider two qubits, both initially |0⟩. Apply a Hadamard gate to the first qubit (q0), putting it into (1/√2)|0⟩ + (1/√2)|1⟩. Now apply CNOT with q0 as control and q1 as target.

- If

q0is|0⟩,q1remains|0⟩. - If

q0is|1⟩,q1flips to|1⟩.

This creates the entangled state (1/√2)|00⟩ + (1/√2)|11⟩ (a Bell state). This state means if you measure q0 as 0, q1 will always be 0. If you measure q0 as 1, q1 will always be 1. Their fates are intertwined.

# quantum_cnot_entanglement.py

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, transpile

from qiskit_aer import AerSimulator

simulator = AerSimulator()

# Create a Quantum Circuit with two qubits and two classical bits

circuit = QuantumCircuit(2, 2)

# Apply Hadamard gate to qubit 0 (control)

circuit.h(0)

# Apply CNOT gate with qubit 0 as control and qubit 1 as target

circuit.cx(0, 1)

# Measure both qubits

circuit.measure([0, 1], [0, 1])

# Compile and run the circuit 1024 times

compiled_circuit = transpile(circuit, simulator)

job = simulator.run(compiled_circuit, shots=1024)

result = job.result()

counts = result.get_counts(compiled_circuit)

print(f"Counts after H and CNOT (1024 shots): {counts}")

# Expected output: counts for '00' and '11' only, roughly 50/50python quantum_cnot_entanglement.pyCounts after H and CNOT (1024 shots): {'11': 506, '00': 518}Notice how only 00 and 11 appear. You will never see 01 or 10 because the qubits are entangled. This non-classical correlation is what gives quantum computers their power for certain algorithms.

Key Differences Summarized

Here’s a table-like summary of the core distinctions:

| Feature | Classical Logic Gates | Quantum Logic Gates |

|---|---|---|

| Information Unit | Bit (0 or 1) |

Qubit (` |

| State | Definite (0 or 1) | Probabilistic (superposition, collapses on measurement) |

| Operations | Boolean functions | Unitary transformations (rotations in a complex vector space) |

| Reversibility | Often irreversible (information loss) | Inherently reversible (no information loss) |

| Key Phenomena | Determinism | Superposition, Entanglement, Quantum Interference |

| Copying State | Trivial (bits can be easily copied) | Impossible (No-Cloning Theorem) |

| Example Gate | AND, OR, NOT | Hadamard, Pauli-X, CNOT |

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding these differences is crucial for several reasons:

- Algorithm Design: Quantum algorithms (like Shor’s for factoring or Grover’s for search) leverage superposition and entanglement in ways classical algorithms cannot.

- Computational Power: For specific problems, quantum computers promise exponential speedups because they can explore many possibilities simultaneously due to superposition and exploit interference patterns.

- Hardware Constraints: Building and maintaining quantum computers is immensely challenging due to the delicate nature of qubits and the need to protect them from environmental interference (decoherence).

- Error Correction: Because quantum states are so fragile and cannot be simply copied, quantum error correction is far more complex than classical error correction.

Conclusion

Classical logic gates are the bedrock of our current digital world, operating on deterministic bits and following Boolean rules. They are the epitome of predictable computation. Quantum logic gates, on the other hand, step into a realm of probability, superposition, and entanglement, manipulating qubits in ways that defy classical intuition but unlock incredible computational potential for specific tasks.

As you venture deeper into quantum computing, remember that while the gates may share names (like NOT), their underlying mechanisms and implications for information processing are profoundly different. The journey from classical bits to quantum qubits is not just an upgrade; it’s a paradigm shift, and understanding these fundamental building blocks is your first step into a new era of computation.